*looks at calendar* Wow, it’s been a while since the last time I was here. I have a good excuse- I’ve been busy working on my PhD! I just started my fifth year, so although I still have a little ways to go, I’m finally about to enter the home stretch. Naturally, I’ve started thinking in earnest about what I want to do afterwards, and I’ve come to realize two things: 1) 99% of research is desperately trying to figure out why nothing is working and gradually realizing that no one, not even your PI, has the answers, and 2) doing science isn’t nearly as fun as thinking and writing about it. So I’m going to play to my strengths (and save my sanity in the process) by pursuing a career in science writing. To that end, I’ve decided to revive this blog and use it to regularly write layperson-friendly articles about interesting scientific topics. The obvious place to start is with my own research project, so without further ado, I’m going to tell you a story about a microbe I’ve become very well acquainted with over the past few years: Enterococcus faecium.

The star of the show

Just like there are many different types of people, there are many different types of E. faecium. There’s the friendly commensal kind who live in your gut and are a normal part of a healthy gut microbiome, which helps you digest food and protects you from pathogens. And then there’s the deadly antibiotic resistant kind, which are commonly found in hospitals and cause infections in high-risk patients who are being treated with antibiotics.

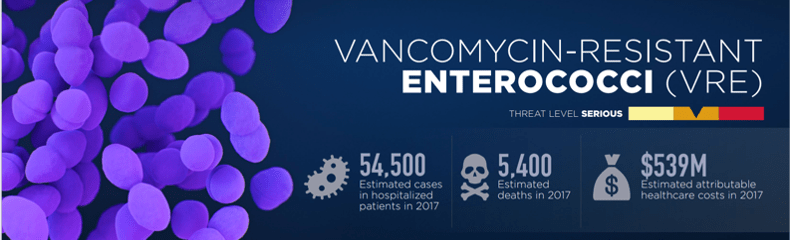

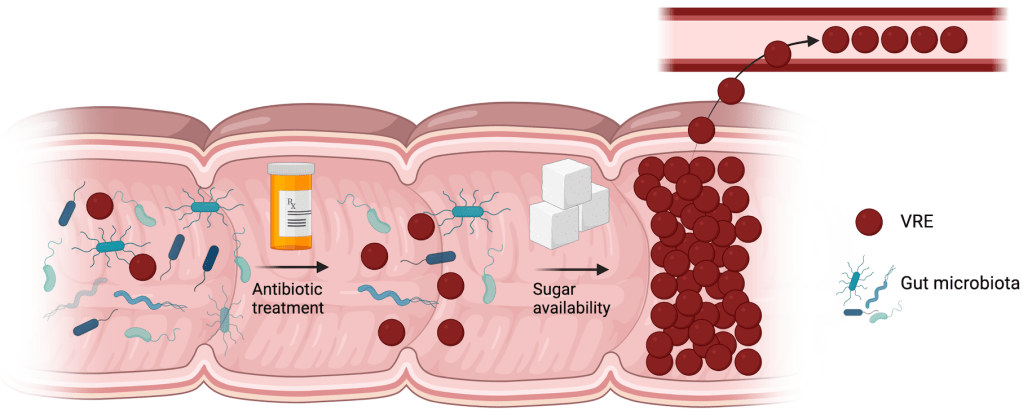

The above graphic is from the CDC, and it shows just how deadly VRE can be. Hospitalized patients who are being treated with antibiotics are at the greatest risk of developing a VRE infection, because the antibiotics will kill off gut microbes in addition to their intended target, freeing up prime bacterial real estate. Without the protective barrier of the gut microbiota, VRE is free to grow and spread in the now much less populated gut. Sometimes it grows so much that there’s not enough room in the gut anymore and it spreads to the bloodstream- this is called septicemia, and it’s a very, very bad thing to have. Once bacteria get into your blood, it’s extremely difficult to get rid of them; hence why so many people die from VRE, and why I’m trying to find ways to prevent VRE from getting to that point.

Many bacteria, few resources

All bacteria need to consume nutrients in order to grow. Whichever bacteria becomes most abundant in a microbial community depends on the abundance of different nutrients and their ability to use them- this is called the nutrient niche hypothesis.

In a struggle for survival between the gut microbiota and VRE, the microbiota will win- until their population is decimated by antibiotics. In the aftermath, as the survivors struggle to rebuild, VRE comes in and starts consuming resources… and in the modern Western diet, there are many, many different resources that VRE is particularly suited to take advantage of.

Namely, sugars. Lots and lots of sugars.

Sugar: it’s bad for us, but great for VRE

Sugar consumption has increased by quite a lot over the past hundred years or so, both in terms of overall amounts and the variety of sugars being consumed. Another thing that has increased over the same time span is the number of different sugar transporters and sugar metabolism genes that VRE has. We don’t think this is a coincidence: we think that VRE has evolved to take advantage of increasing sugar availability, and that their ability to metabolize many different sugars gives them a competitive advantage over the gut microbiota. They devour the available nutrients before the microbiota has a chance to fully recover from the antibiotics, expanding quickly to dominate the gut and eventually spread to the blood.

The focus of my research is identifying new targets we can use to combat VRE, to reduce their population in the gut before they can spread to the bloodstream. In particular, I’m looking at their sugar metabolism genes to see whether any of them are useful targets. The idea is that it may be possible to prevent VRE from growing and taking over the gut by either blocking their ability to take in certain sugars or by blocking a particular step in the process of breaking down a sugar after VRE has taken it up, the latter of which will lead to toxic effects on the bacteria due to intermediate products piling up.

So, that’s a broad overview of what I’m doing. I’ll be back with more posts about some of the specific things I’ve been doing in the lab. I’m looking forward to sharing them with you!

Update: check out this blog post about my latest paper!